Morewood Zula

When South African brand Morewood started out, it was a classic example of necessity being the mother of invention. They were founded by elite downhill racer Patrick Morewood, who struggled to find bikes that could take the abuse of regular DH riding and decided to start making his own.

With strong adherence to the KISS principle (keep it simple stupid), the bikes were made solid, stiff and with as little fuss as possible—especially when it came to suspension design. Over the last decade they’ve built a strong reputation amongst those in the know for building durable, reliable, no-nonsense bikes that continue to put a smile on your dial when many other bikes are off spending time in the workshop. From their DH roots Morewood expanded their range to encompass the full spectrum of MTB disciplines, and although Patrick Morewood sold his interest in the company a few years ago, his legacy still inspires the design language of the bikes which bear his name.

Whilst there’s now a few Morewoods using Dave Weagle’s Split Pivot four-bar layout, the company still believes in the beauty of a well-executed single-pivot suspension system, and the 100mm travel Zula sports just such a design. The Zula started its life as a cross-country racer with 26-inch wheels, but its aggressive geometry and dependable construction saw plenty of riders press them into double duty as short travel trail bikes—I remember lusting over a friend’s black and red Zula on many occasions.

In 2013 the Zula took on the slightly bigger 27.5 wheels as well as further updates to the geometry whilst still keeping its 100mm of suspension—in a world of ever-increasing travel, I was interested in testing their ‘less is more’ approach. Being a boutique frame-builder Morewood don’t sell complete bikes, however Australian distributor Pushie Enterprises kindly sent a bike kitted out with many of their in-house brands for me to abuse on our far-from-XC local trails.

A frame only will set you back $1,900, which is pretty reasonable for a non-mainstream brand. Although build kits are customisable, and as such prices are quite variable, the Shimano XT equipped test bike would set you back around $4,990. Just make sure you spec it with a trail-worthy short stem and wide bar, rather than an old-school XC setup.

Crossover, not Cross-Country

At first glance the Zula seems somewhat anachronistic; think 100mm 27.5er and your first thought is of a race bike. If that’s the case, then the Zula is more of a marathon runner than a sprinter because the frame/shock weight of 2,820g (size large) certainly can’t compete with the plastic fantastic wonder bikes of the XC World Cup, and that’s obviously not its intention.

The geometry tells a very clear story; short 430mm chainstays, 620mm top tube, a particularly low 25mm bottom bracket drop, and a slackish 68.5-degree head angle with a 120mm fork, all add up to a bike intended for going fast in the name of fun, not for a VO2 max sufferfest.

Some of you may find it a little odd to run mismatched suspension front and rear, but in fact there’s a long history of bikes set up just like this; the Orange Blood, GT Distortion, Banshee Spitfire, Rocky Mountain’s ‘BC’ editions, and every hardtail ever made come to mind. The extra front travel improves front wheel traction in the rough and makes the bike more forgiving at speed and on steeper trails, whilst the shorter rear travel maintains snappy acceleration and a poppy ‘feel’; it’s the mullet of the MTB world, with business at the front, and a party out back. Put it into this context, and the Zula suddenly makes a whole lot more sense. Built up with quality but not outrageous parts we ended up with a short travel 27.5-inch trail bike that weighed 12.3kg without pedals, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with that.

If I’m going to treat the Zula as a trail bike, and I believe that’s appropriate, I need to start by pointing out one absolutely glaring omission by Morewood; there’s no routing of any kind whatsoever for a dropper seatpost. Previously we’ve often only seen them on longer travel, 120-140mm bikes, and you might argue that the 100mm travel Zula doesn’t warrant a dropper post; or at least you might until you’d ridden it. Even if it was a pure race bike, we’re starting to see top XC competitors experimenting with dropper posts, willing to accept their weight penalty for the superior handling on offer.

In our opinion, modern mountain bikes need dropper posts, and we can’t understand why Morewood didn’t tack on a few well-placed guides or strategically drill a couple of little holes for the cabling. The only saving grace is that the frame shape allows you to quickly and easily cobble together a setup with a few zip ties and/or stick-on guides—it’ll be relatively neat and completely workable, but also very workmanlike. This is exactly what happened with our test bike and I can’t imagine why you’d want to ride the Zula any other way.

Simple Sophistication

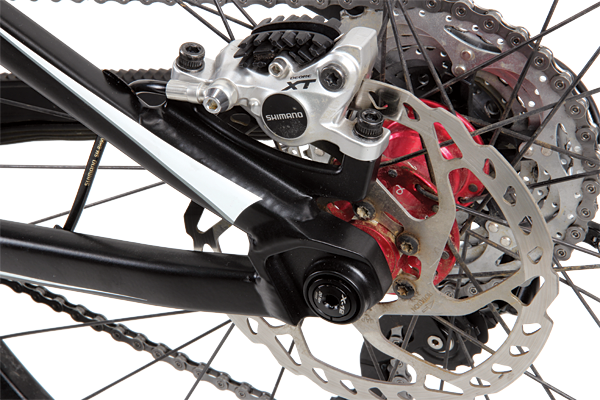

The Zula’s frame profile is refreshingly clean and simple, with mostly straight lines and squarish tubes. Cable routing is external and very neatly attached with screw-in guides under the down tube, and thankfully for those averse to creaking noises, it sports a traditional threaded bottom bracket instead of some press-fit debacle. Beneficial advances such as post mount brakes, a tapered head tube, and Syntace X-12 thru axle rear end have all been included, but there’s something very traditional and pleasing about the Zula’s appearance—heck, it’ll take a water bottle on the right side of the down tube, and the frame triangles actually look like triangles!

From the cranks forward it’s a decidedly stiff frame, however a little flex starts to become apparent as you get closer to the rear wheel. Some designers will make their frames with maximum stiffness from end to end to make handling as predictable as possible, whilst others are adamant that building a little flex into the back end helps to keep the rear wheel tracking on rough ground, and also helps to give the bike a bit more energy coming out of high-G turns as the frame springs back to neutral. Whether intentional or not we can’t say, but this undoubtedly plays a part in the handling characteristics of the Zula.

In terms of construction quality, the welding isn’t the absolute neatest we’ve seen. We had an issue with our test bike where the weld between top tube and seat tube had too much penetration. This caused a slight bulge inside the seat tube and we couldn’t insert a seatpost past this point without having the tube reamed. Whilst it’s great that Morewood are trying to keep at least some of their production including the Zula in South Africa, their Taiwanese made frames are finished to a much higher standard. That being said, the paint finish is nice and thick, the colour scheme is tasteful, and overall it’s a good looking and solidly made bike. We’re also told that the local Morewood distributor would normally fix up any discrepancies (such as our seatpost reaming issue) before sending a bike out—it’s just this one went out in a hurry to meet our review deadline.

The rear triangle is a single one-piece unit, with a large hollow brace between the pivot and rear shock mount. This member also wraps around the seat tube to keep this vital area free from lateral movement. There’s no bridge between the seat stays and the lower swing arm brace is quite small. As a result, there’s plenty of space for big volume tyres, even with mud room taken into account.

Morewood’s ‘Stable Pivot Interface’, or SPI Lite, provides the vital link between the Zula’s front and rear halves, and it really is a beautifully simple design. The entirety of the pivot hardware consists of two large bearings, two washers and the two threaded halves of the pivot bolt; think of these six pieces the next time you have to service the bearings on your multi-link suspension or are cursing in frustration at that creaking noise you just can’t seem to locate.

The pivot itself is a large hollow unit that’s designed to maximise stiffness with minimal weight, and the whole thing can be disassembled with two allen keys. Antoine de Saint-Exupery once said, “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away”, and in that context Morewood’s SPI Lite pivot system has to be perfection realised.

There’s also a lot of hype these days around the latest multi-link, eccentric pivot, sliding rail, virtual pivot point, all singing and all dancing suspension designs. I’m no luddite and welcome advances in suspension technology, but let’s not forget that every suspension design has its own pros and cons, and examine them on their merits, not by their ‘type’.

In essence, bicycle suspension has to balance the often conflicting attributes of pedalling efficiency, bump absorption, pedal kickback, and braking neutrality. I believe that the main reason single pivot designs are less popular these days is that all of these attributes are controlled by the exact location of just one pivot. You can’t rely on multiple variable points to tweak the axle path, or leverage ratio, or anti-squat; either you strike a good balance with that single pivot location, or you don’t. Of course we also need to take into account that different riders or riding styles will have different priorities in terms or ride feel, but the reality is that despite all the hype, a well-executed single pivot suspension design works perfectly well. Perennial favourites like the Santa Cruz Heckler and Superlight, and the Orange Five, are cases in point and the Morewood Zula deserves a place on that list with them.

Just Ride

From the first turns of the cranks the Zula feels familiar, like slipping into a pair of jeans you’ve been wearing for the last few days. There’s no weird geometry, no complex leverage curves, nothing you need to get accustomed to; simply set sag, set rebound, and go ride—it’s that simple. Actually that’s not true, because the Zula has such an enthusiastic nature to it that you won’t just want to ride, and ride a lot, but you’ll want to ride fast. Each pedal stroke sees it lunging forward, as if it’s been straining at a leash and has finally broken free; now it’s time to get out and play with the trail until there’s nothing left in the tank, then you can meander home, curl up and rest until the next ride opportunity presents itself.

Single pivot suspension designs behave quite differently when you vary the chainring size (more so than some other systems), and although our test bike came with a 2x10 drivetrain we really think the Zula would work best with a single 32-34 tooth ring up front and a wide range cassette. The pivot location is optimised to provide the best balance of pedal kickback and efficiency with this setup, and a 42 tooth rear sprocket would still allow you to ride up anything that didn’t closely resemble a wall.

Standing and pedalling up steep trails necessitated using the trail mode on the Fox Factory CTD shock, but for just about everything else the open setting works great; supple without being soggy or inefficient. Some bikes feel almost disconnected from the trail but the Zula instead is constantly communicating with you about the size and speed of bumps, the amount of travel you’re using and how much harder you can push it; it’s thoroughly engaging from start to finish. Pushed hard into turns you can feel a little lateral flex at the rear wheel, but it doesn’t detract from the ride quality; quite the opposite in fact, with a definite sense of accelerating out of corners as the frame flexes and then rebounds. This flex is also minimal enough that on straighter sections of trail the rear wheel can be placed accurately, and once on line it stays firmly planted.

The Zula tackles technical climbs very well; the harder you push on the pedals, the harder the rear wheel digs in as it hunts out whatever traction it can find. There’s definitely a little feedback through the pedals which some riders may not like, but personally I’d rather this lively, reactive feel than something which flattens the trail to the point of feeling disengaged with what’s happening under your wheels.

When the trail points downhill the Zula’s slack angles, low bottom bracket, and short rear end keep it feeling stable, but still nimble enough to loft the front wheel or pop over a rock or off a step down without pitching your weight too far forward. The Zula’s aggressive nature means you’ll definitely push the shock’s O-ring off the shaft on plenty of occasions, but you’ll have a hell of a lot of fun in the process and you’ll quickly learn to ride more smoothly rather than slamming the bike into the ground off every drop. It’s also worth noting that the axle path has a large rearward component, so small to midsized bumps, especially those with square edges, are gobbled up much better than you might expect from the travel numbers alone.

The Zula is one of those bikes which seem to defy logic. Judge it on paper alone and it simply doesn’t stack up with many of the current crop of high-tech trail bikes. It’s certainly not cheap, it’s relatively heavy, rear travel is limited, construction quality could be improved, and the suspension design is so simple as to look almost outdated. In the real world, however, it’s a whole different story. Despite these apparent shortcomings, Morewood’s little beastie provides a fast, reliable and utterly engaging ride that’ll never fail to have you grinning with glee. Anachronistic it may be, but the Zula is one hell of a good short travel trail bike.

Thumbs up

Simple but thoroughly effective design

Fun and great handling

Well priced for a ‘non-mainstream’ brand

Thumbs down

Quality of the finish is lacking

Lacks dropper post routing

Specifications

Frame: Formed and butted 6000 series alloy

Shock: Fox Factory CTD 100mm Travel

Fork: RockShox Revelation 130mm Travel

Headset: Accros semi-integrated

Handlebars: Loaded AMX alloy 740mm

Stem: Loaded AM/XC Flat Alloy

Shifters: Shimano XT

Front Derailleur: Shimano XT

Rear Derailleur: Shimano XT

Cassette: Shimano XT, 11/36 10-speed

Chain: Shimano HG73

Cranks: Shimano SLX 26/38

Bottom Bracket: Shimano (threaded)

Pedals: N/A

Brakes: Shimano XT

Wheels: Loaded X-lite

Tyres: Schwalbe Racing Ralph 2.25

Saddle: SDG

Seatpost: Loaded X-lite alloy

Weight: 12.3kg without pedals (Large frame 2,820g)

Available Sizes: S, M, L (tested) and XL

Price: $1,900 frame only (approx. $4,990 as tested)

Distributor: Pushie Enterprises (02) 9560 7841 / www.pushie.com.au