Orbea Occam H30

Although not a household name in Australia, Spanish brand Orbea have a long and illustrious history in the world of road cycling as well as XC racing. They supplied bikes to Julien Absalon for five of his winningest years, and currently sponsor Elite athletes like Catharine Pendrel, amongst others. In Orbea’s own words the Occam 29 is, “Perfectly suited for trails and long distance XC riding.” It offers 105mm of travel at the back mated to a 120mm fork (a 140mm fork is optional).

With three alloy and three carbon models to choose from, prices range from $3,399 up to a whopping $12,599. It’s a broad price spread but there’s no true ‘entry level’ model, but then Orbea pegs themselves as a premium brand, so budget-conscious shoppers are likely to be looking elsewhere anyhow. So how does feedback from some of the fastest riders on the planet shape the nature of a cross-country trail bike? That’s the exact question we set out to answer with our $3,699 Occam H30.

Cutting Looks

I think it’s fair to say that the Occam looks purposeful and fast; its straight tubes don’t waste precious metal getting from one junction to another, and the distinctive humpback top tube almost mirrors the silhouette of a rider hammering away at the pedals. The bike is named after William of Occam who devised the theory known as Occam’s Razor, which states that the simplest solution to any problem is usually the correct one. Orbea have, in many ways, not just given his name to the bike, but built it around this principle; clean lines, proven technology and no unnecessary frills like extra suspension travel or adjustable geometry.

Orbea has certainly put together a tidy package. There’s a nice thick coat of matte paint, very tidy welds and quality machining on the linkage as well as etched-in torque specs on the pivot hardware. The expanding collet main pivot is offset to allow room for a front derailleur and it can be serviced without needing to remove the cranks—a clear bonus when maintenance calls. As you’d expect with any self-respecting cross-country bike, there’s room inside the frame for a full-size water bottle.

I’ll admit to being surprised but the Occam has one of the stiffest frames we’ve come across in recent times; no small feat when you factor in the longer chainstays of a 29er. At 13.3kg for the complete bike (minus pedals) or 2,970g for our medium frame, it’s quite a respectable weight without being feathery-light or feeling flimsy in any way.

Triple ring drivetrains may have fallen out of favour in recent years, but having the widest possible gear range is a great thing on a bike designed to cover substantial distances, especially in varied terrain. It’s also worth noting that the front derailleur is a traditional band mount, so should you wish to go 1X in the future, there won’t be an unsightly mounting tab hanging off your frame. It’s a shame that the exit port for the internally routed front derailleur cable is so small; cable changes involve quite a bit of fishing as a result.

The Maxxis Ardent Race tyres on our test bike definitely favour straight line speed; they roll noticeably better than the regular Ardent. This befits the intentions of the bike but cornering bite is lacking too, delivering a few pulse-raising moments if you push them like a more aggressive tyre. There’s a reasonable amount of free space around the 2.2 rear tyre, so you could always run something more substantial if you wanted, although the 19mm internal width of the rims won’t offer much support for wider rubber. Combine a wider tyre with some broader rims and you’ll fill the available chainstay clearance pretty quickly.

As a smaller brand in a global market, Orbea recognise that they’ll likely be at a price disadvantage compared to the biggest players; their economies of scale simply won’t allow them to offer the same value componentry as the biggest players. Instead, what they offer is a semi-custom build option. You go into a dealer and via their website choose the frame size and components you want bolted onto your bike. The order is then sent directly to Orbea in Spain, and the bike is custom assembled to your requirements and air-freighted to Australia. The whole process takes about three weeks – some bikes take longer to get shipped around Australia – and what arrives is a unique bike that hasn’t been sitting on a shop floor for six months, and it’s exactly the way you want it.

One of the challenges of being a bike reviewer is constantly swapping between often very different styles of bikes. There’s usually an adjustment period on a new ride and the ride characteristics can contrast sharply from one bike to the next. In some cases the ride qualities are so distinct that you’ll get a good feel for the geometry before you even see the figures on paper. The Occam was a classic example; it felt quite long at the back, relatively steep at the front, and low through the cranks. The numbers bear this out; its 70-degree head angle is very much about precision and rapid response, whilst the 445mm chainstays (they seemed to measure a bit longer than that) keep your weight centred for climbing and eating up long distances.

These numbers are conservative, almost old school by some modern standards, yet Orbea are very progressive when it comes to the geometry of some of their other models—take the gravity enduro oriented Rallon for example, which features very aggressive geometry. The Occam’s geometry is clearly aimed at the XC end of the trail spectrum. If you’ve felt neglected by recent trends towards slacker head angles, the Occam may well fit the bill. It contrasts against many competitors by delivering a ride that’s tailored towards those who want to go fast without gravity assistance.

The cockpit also bears this out, with an almost flat 710mm wide bar mated to a 70mm stem (90mm on the large) to help give extra breathing space and keep your weight forward for climbing. The Occam is clearly a burly XC bike, not a pared down gravity rig.

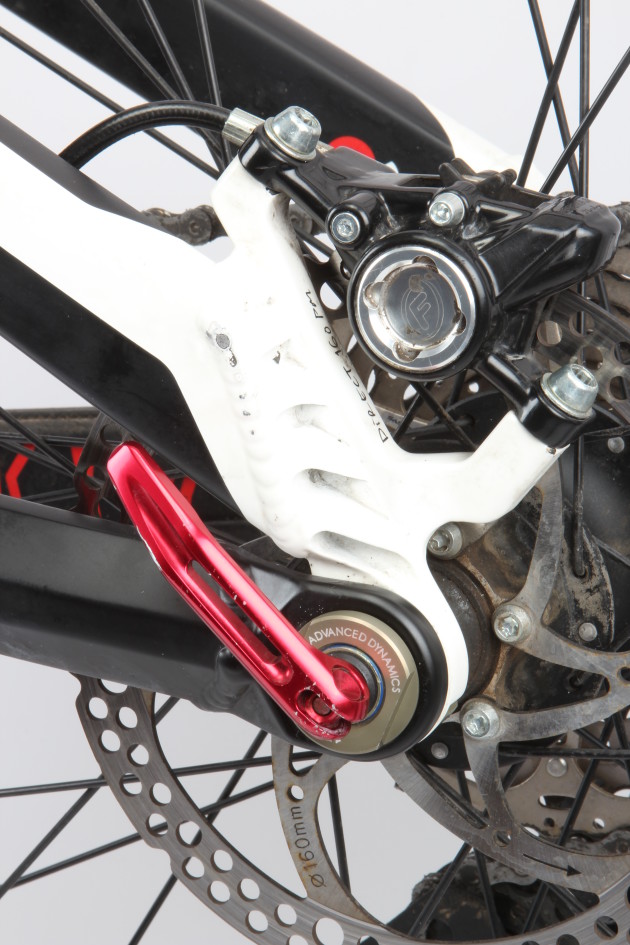

Despite its cross-country proclivities, I have to say that the omission of any dropper post routing is a weakness to my mind. It may have XC leanings, but the Occam is first and foremost a trail bike, and the extra cornering speed and descending confidence gained by getting the saddle down and out of the way would add another level of versatility. Sure, a few cable ties will do the trick but it’s not the neatest solution. I’m also in two minds about the Formula C1 brakes. The pad clearance is much better than the older Formulas and they needed zero adjustment to remain drag free during our test. They’re also quite easy to modulate, with a steadily progressive application of power right up to their maximum. That maximum power does, however, feel noticeably lower than many competing brakes; they’ll be just fine if your trails aren’t too steep, but an upgrade would be a good idea if you live in a particularly hilly area.

Less is More

One area where the Occam did surprise was with the overall quality of its suspension; it definitely feels like there’s 15-20mm more travel that the claimed 105mm. You can obviously push past its limits if the hits are coming fast and large, but overall it feels far more composed than any bike with a mere four inches of travel has a right to.

Whilst the custom tuned CTD shock has three distinct damping settings, the firmest ‘climb’ mode is still a fair way from being locked out. The folks at Orbea clearly believe that traction will always trump mechanical efficiency for a trail bike. That being said, with a relatively small amount of travel on offer all of the three damper settings provided excellent seated pedalling efficiency; even out of the saddle there’s little enough movement to keep all but the most hardened racing snake happy. For me, the suspension sweet spot was with about 25% sag with the shock fully open—set it and forget it.

At a glance the suspension may look like a linkage driven single pivot but the Occam uses a rear pivot that’s concentric with the wheel axle. In principle it’s very much like Dave Weagle’s Split Pivot or Trek’s ABP. The idea behind this configuration is to separate braking and pedalling forces from the suspension action. It certainly works, but as always with suspension the devil is in the detail. From my experience I’d say that Orbea’s take on the design leans more towards pedalling efficiency; it doesn’t feel as active over braking bumps as its competition, but it edges them out in terms of power transfer. Our test bike comes with a 5mm rear skewer (remember those?) but it can be replaced with a 12x142mm thru-axle if desired at the ordering phase, and higher spec versions of the Occam come with a thru-axle as standard.

In terms of overall ride feel, the Occam 29er is exactly what you might imagine from the descriptions above. The steep head angle allows it to respond precisely to steering inputs, and combined with the 29er length chainstays, it puts you in a very central seated position. On flat or undulating terrain you really only need to focus on pedalling without having to use significant amounts of body language to keep both wheels planted and the bike heading exactly where you want.

Even when the trail turns more sharply uphill, you can remain seated and spin the cranks to maintain forward momentum. Combined with the rollover ability of the big wheels, it’ll tackle most climbs efficiently and effectively. It’s only when things get really chopped up or steep that it struggles for traction, and this is partly due to the less aggressive tyres. The steeper head angle also keeps the overall wheelbase in check, so it’s actually pretty nimble in tight trails too, an area where a more raked out 29er would be at a natural disadvantage.

Razor’s Edge

Steep and rough descents, however, are not the natural home of the Occam. All of the things that work in its favour in other circumstances work against it on the downs. The long chainstays and sharp steering angle put you that much closer to flying through the air and then kissing the dirt, especially as speeds increase. If you’re prepared to rein in the pace a little, it’ll get you down most things without incident, but excessive bravado will inevitably be rewarded with excessive bruising. This shouldn’t be an issue for the would-be Occam owner, who’ll likely pull back on the descents in order to kill it on the flats and nail the ups, but once again it’s a reminder than the big Orbea is about miles covered, not metres descended.

All told, the Occam 29 H30 stands out from the crowd. Firstly because it’s not a bike that you’ll see under every third rider at your local trailhead, and secondly because of its focused intentions. Rather than trying to be a jack of all trades, or even a mini downhill bike, its purpose is to allow you to eat up long distances, often over quite rough terrain, and to do so with maximum efficiency and comfort. Its combination of highly competent suspension, agile handling and efficient geometry means it’s the perfect bike for an XC rider wanting to push their boundaries, and to do it on a bike that is not only very well made, but made just for them.

Thumbs Up

Effective suspension travel

Excellent frame rigidity

Eats long distances with ease

Thumbs Down

No guides provided for a dropper post

Brakes lacking in ultimate power

Spec for dollars not as sharp as some

Specifications

Frame: Hydroformed triple butted alloy

Shock: Fox Float CTD 105mm Travel

Fork: Fox Float CTD 120mm travel

Headset: FSA Integrated

Handlebars: Race Face Ride 710mm

Stem: Race Face Ride alloy 70mm

Shifters: Shimano Deore

Front Derailleur: Shimano Deore

Rear Derailleur: Shimano SLX

Cassette: Shimano HG50, 11/36 10-speed

Chain: KMC X10

Cranks: Shimano Deore 22/30/40

Bottom Bracket: Shimano Deore

Pedals: N/A

Brakes: Formula C1

Wheels: Mavic XM119

Tyres: Maxxis Ardent Race 2.2

Saddle: Selle Italia Q

Seatpost: Race Face Ride Alloy

Weight: 13.3kg without pedals (Medium frame 2,970g)

Available Sizes: S, M (tested) and L

Price: $3,699

Distributor: BikeBox (03) 9555 5800 / www.orbea.com