From mixing it with Sinatra in Hollywood to performing at the Olympic Games closing ceremony, Hans has pretty much done it all. Despite the fame he comes across as a humble, intelligent and artistic man, with a great deal of integrity and passion bundled in.

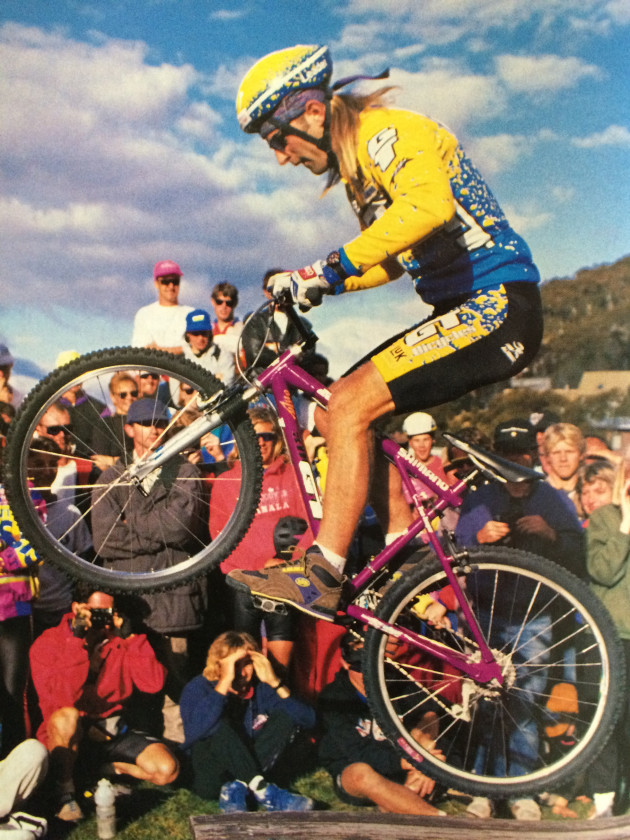

Some may find it hard to believe but Hans Rey is set to turn 50 soon, but he’s still doing his thing and still in the limelight—something few extreme athletes attest to at this stage of life.

Where did it all begin?

“I was born and raised in Germany and there was a motorcycle trials club where I lived in Emmendingen in the Black Forest. We just wanted to imitate them but were too young to ride motorcycles, so we started riding trials—bicycle trials was very much a European sport.

“In the mid ’80s some American trials riders started to show up at the European Championships. They were fully sponsored but were nowhere near the top 20 or 30. One of those guys invited me to come over to the US—they had a new sport called mountain biking. Back then they had MTB stage races, where riders had to ride trials, downhill and then cross-country all on the same bike.

“I’d officially retired from riding to go to university but went to America anyway; I thought it would be a great finish to my career. I took a semester off school for it but never went back.”

You were an immediate hit?

“I got instant recognition and sponsorship opportunities from Swatch and GT Bicycles. Swatch wanted me to tour all over America. I took up their offer and one year became two, then three and now it’s been 28 years.”

You are Swiss by nationality, so did the Swatch link come from this?

“In a roundabout way. In 1985 I organised a competition in my hometown and Swatch Germany sponsored it. Then in 1986 I went to do national service with the Swiss military and one of the commanders happened to be the marketing boss at Swatch.

“We got along and when he became the GM of Swatch Germany, we did a couple of projects together. I appeared on a very big German TV show and wore a Swatch sweatshirt.

“Right after that I went to America and by coincidence my American friend got a phone call one morning from Swatch. They were shooting an advert and needed two trials riders that afternoon—that was the beginning of a very long sponsorship.”

What has contributed to your long-term success?

“Creative marketing has kept me alive right up until now. I’m a one-man show, and the people who work closely with me know that I’m not just ‘some mountain bike guy’. With me you get a built in PR agency, a team manager, advertising consultant—the whole package.

“It means I play more of a business role than the average sponsored rider wants to, but it pays off in the long run and I feel that’s my big advantage. I always try to be creative—if I didn’t keep throwing wood on the fire I think my fire would have been extinguished by now.”

The sport has evolved and changed dramatically, how do you manage to stay relevant?

“I’ve never assumed a sponsor will continue supporting me because of my riding or because I can put on a trials show. That’s always been a part of my package but I keep changing things—like blending mountain bikes and travel. This move delivered exposure that stretched well beyond the bike industry.

“You have to keep an open mind, take risks and try things out. In the early ’90s it was all about cross-country racing and a little bit of downhill. Trying to convince a team manager to also sponsor a trials rider, well they couldn’t really grasp it. Most came from road cycling and had a hard time with fat tyres anyway—cross-country was closest to their culture. Often I was the only one, and in some ways I had it easier to make my name, although I also had to pave the road for the generations that followed.

“Trials offers great flexibility as you can do a show anywhere; from a TV studio to a bike shop or a wedding. Others saw the success I had with GT and the media exposure. In many ways it opened the door for trials riders to approach bike brands—it made things a little easier for them.

“This paved the way for people like Danny MacAskill and the things that Red Bull does now. Swatch was the first corporation to really hone in on extreme sports—this was way before Red Bull even started dealing with that stuff.”

How has the internet and social media changed things and what do you make of today’s YouTube MTB stars?

“There’s a lot of material out there these days, but even though the cameras are a lot better these days, it remains hard to come up with really good material. Danny MacAskill has YouTube but for me VHS was the medium and I basically became famous through video.

“One year the (late) GT boss Richard Long said to me; “Hans, it’s so difficult to explain what you do on a bike, why don’t we do a video?”

“So we filmed some tricks and urban riding—it was way ahead of its time. There were only a few MTB videos out back then and they were usually race coverage and pretty boring. Our video had cool music, lifestyle as well as some fun and goofiness. It was short enough that people wanted to see more, and came at a time when it was hard to share this stuff.

“People would take the videos to parties, show everybody and wear them out. It was a new era and those videos really changed things for me. A lot of that material ended up on TV and I became really well known—I was on my own there for a long time.

“To an extent I think it’s a little bit simpler now for Danny. With the powerhouse of Red Bull behind him, he can set himself apart from every other kid who’s posting stuff on the internet. It takes a big budget to create stuff like Imaginate.

“I’m really happy with what Danny has done, and what he’s done for our sport. I often think about how many parallels there are to my career in the VHS days.”

You’ve been with the sport from just after its inception right through, how do you sum up its changes and development?

“Mountain biking has always been a very liberating sport. In the early ’90s, a generation made it really big and persuaded the industry to put all of their marketing dollars behind racing. That has largely gone now.

“Many have realised that it’s not all about racing. Manufactures may sell millions of bikes but only a small percentage will be used for competition. That’s why I always did my shows in an urban environment; I took things away from the mountain. I’ve always felt that the race driven hard-core aspect kind of missed the point, and that original spirit of the clunkers was becoming lost. Competition can be great but when you worry too much about who won and who lost, you miss out on the spiritual part of mountain biking.”

What made you decide to blend riding and travel for your ‘Adventure Team’ concept?

“I always loved travelling and though it would be cool to use my trials skills in real situations; like on an expedition on really technical terrain—I liked the idea being a modern day Indiana Jones.

“History and culture also intrigued me, so I thought combining all of those things would really make a good story. It also allowed us to capture and audience that was not necessarily hard-core bikers—people who just liked the storyline or the scenery.

“It was also a way to stay in the media. As a sponsored athlete you are usually measured by what you bring back to them, and media results are a good measure of your worth. If you win a race you’re lucky if the magazine even writes about you, but if I do an adventure and get a six page story in a publication, then that’s a great result.

“In recent years I’ve tried to combine these adventures with my Wheels 4 Life charity projects or to do things with IMBA (International Mountain Bike Association) to help spread the word on flow trails.”

So you do work for and support IMBA?

“Yes, I believe in what they do. They give mountain bikers a voice and fight for our rights. They educate people about trail use and trial building as well as educating land managers and representing us by lobbying politically.

What’s your take on flow trails?

“Currently, many man made trails can be fun for experienced riders but they are very inconsistent and can be dangerous for beginners—what’s ‘flow’ to one rider can be a nightmare to others.

“The Eskimos have about 12 different words for snow; it varies according to its consistency. Mountain bikers haven’t yet refined their language to this degree. So along with top trail builder Didi Schneider, we came up with the term ‘flow country’ to describe a particular type of trail. We immediately went to IMBA with it; we didn’t want it to be a ‘Hans and Didi’ thing as the aim was to benefit the whole industry.

“Flow country is a mix between a singletrack and a giant pump track. It’s never steep, never extreme and never dangerous. You can ride it with any kind of bike and any skill level. I’m always interested in getting new people into the sport and a flow trail can be enjoyed by riders of all abilities.

Will we all be riding on man-made trails before long?

“I think there will always be both kinds of trails. As popular and trendy as man-made trails are now, I can see that people will be crying out for natural trails in five years or so.

“The cool thing about man-made trails is that we can get that guaranteed flow. You can have a 10km long rollercoaster with non-stop swoops and turns—it can be addictive and fun.

“People get a great thrill and find the sport this way; it’s not like the old days when we had to climb hills look for trails. That was earning it the hard way when you actually had to be a skilled rider to find good trails. These changes will definitely make mountain biking more popular.”

What encapsulates the spirit of mountain biking for you?

“For me it’s trail riding. Going out and riding singletrack with challenging trails and terrain.

“The other thing is going on my adventures, being the first to ascend Mount Kenya or traversing the Sinai Peninsular—the adventure factor definitely grips me.

“I also get a great satisfaction riding trials. It’s like meditation for me; the visualisation, the emersion, the finesse in pulling off a move, the body control—it’s very satisfying.”

Have things become tougher as you get older?

“Some things get harder, some get easier. You change your goals but I feel as fit as ever when I go on XC rides. I don’t have to attempt four-metre drops in the bike park, but I still do them—just not every time. You definitely don’t heal as quickly.”

“It’s easier in that people know who you are, how you work and how professional you are, although I do have to fight against people’s preconceptions. They think, ‘He should be doing something else at his age’. A lot of my friends retired at 30 because it was expected. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not like tennis or golf where you can retire in wealth—riding mountain bikes for a few more years always beats working a regular job.

“I’m sure some of my sponsors wonder if they need to budget for me for next year, but at the same time they see that I’m still getting exposure and contributing to the sport. There are other ways to do things without being the youngest, the fastest or the most extreme.

“These days you can easily spend $10,000 plus on a bike. Perhaps it’s good to have somebody of my age that inspires the demographic that can actually afford these bikes.”

What’s left on your bucket list and do you have any regrets?

“There are a few things on the list. One of my regrets is that I didn’t jump straight on a plane when the Berlin Wall came down. I was in the US and didn’t have the money for a flight. I wasn’t as spontaneous or savvy in finding cool marketing opportunities back then.

“There are places like Iceland where I’d like to ride and it would be good to go back to Australia and do something in the outback too. I also want to sample the finest trails around the world; I think there will be a lot of opportunities to do this in the next five years.”

Tell us about your Wheels 4 Life charity?

“It’s something I came up with around 2005; supplying bicycles to people in developing countries. We work almost one-on-one and our projects are often quite small but it’s really is amazing to see the changes in people’s lives.

“We have three main target groups; first there are children who need the bikes to get education, as they often have to walk 5-10km to get to and from school. Then there are teachers and health care workers as well as regular people or farmers who need bikes to help them get their produce to markets. So far we’ve given away around 6,500 bikes in 26 countries.

“Often the whole family will use the bike. Even the smallest chores like visiting to the nearest water hole can be 4km each way, so doing things faster and easier makes a huge difference. There was one kid who wanted to become a doctor but didn’t have any jobs locally. He got a job on a construction site in a nearby village and carried buckets of water on his bike all day long. With this he made enough money to finish his studies at university.

“Many of the stories are directly life changing, but we like to focus on overall education and also women; in Africa women are often the driving forces. If they get educated they can make a lot of changes to people’s lives.”

For more about the charity go to: www.wheels4life.org